Passing Through The Keyhole

This essay originally appeared in High Desert Journal in 2020 and was nominated for the Best American Science and Nature Writing award. Unfortunately, the journal has since folded and so I am resharing the story here, with some added illustrations.

Meteoric water is water that has fallen, filled the porous, the permeable, the receptive. Dropped from the sky and collected into the hollowed pock-marks of the earth. It is the linear link from the arc of the heavens to the arc of the planet, dripping groundward to the bone-picked bedrock of creation.

It starts in the nothingness above your head. That empty abyss. The collection of invisible molecules––condensing, growing, and finally descending to our little slice of crust––happens all in that rattling chasm where the top of your head ends and the rest of the cosmos begins. It is existence coaxed from emptiness.

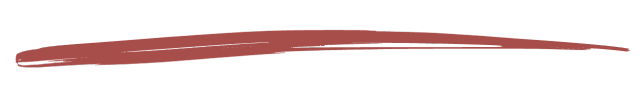

Water discovers landscape through raw touch, slipping fingers into the curved bodies of rock, falling through the open pores of sand, pressing the soft earth to carve channels and passageways. It is an intimate affair in which we are faithfully interwoven.

Water discovers living bodies in much the same way; pressing and parting flesh, separating and dismantling bone, carving down fragile lives. Stone can survive this sort of regular dismemberment. Bodies have a more difficult time.

By late fall 2015, local authorities are calling it an erratic monsoon season in southwest Utah. I had prior reserved a phrase like "monsoon season" for wet, coastal towns, not landlocked North American deserts.

Hildale, a small town of Mormon fundamentalists, sees two hundred-year flood events in a single afternoon. The floods kill 13 people. The cars are swept right off the road. The casualties are mostly children.

That same day, seven canyoneers die in a slot canyon in Zion National Park 15 miles south. A wall of water surges through the canyon. The seven aren't more than a few hundred yards from the vehicles they left parked on the pavement.

I arrive in Utah several months prior to monsoon season, when snowfalls on the lips of Zion Canyon are just beginning their spring runoff, swelling the Virgin River, when the skies are glacially blue and impossibly sunny. My knowledge of rain is what I know of relentless Pittsburgh downpours––water that slowly gathers until it pools into every depression the earth has to offer; surpassing river banks over long stretches of hours or even days, penetrating basements and pouring over freeways in due time. What I don’t know of rain is everything else.

I stand with Tom and Anna––two park rangers, friends––behind the sandstone dorms where they're housed for the summer. We have climbing ropes slung heavy across our shoulders, harnesses like girdles strapped tight around our waists. Tom ties me to the laundry line by weaving a figure-eight knot through the harness loop below my belly button and secures the other end around the pole. Next to the clothespinned underwear crisping in the desert sun, I practice leaning back the way I will in the canyon. The ropes move like water between my palms. I lean back into a low squat, feeling like an awkward bird. Tom says, "You're a natural."

The Virgin River carves Zion Canyon. It is the glimmering thread stitching the landscape together. Starting on Cedar Mountain in southwest Utah and running for 160 miles, it eventually pours into the Colorado River, which pours into Lake Mead. By then the Virgin has dropped 7,800 feet, roughly 48 feet per mile. It drops this way by carrying small pieces of the earth, like pebbles in a shoe, all the way back to the sea. Rivers lower the earth one grain of sediment at a time, exhilarated by the very real dream of the ocean, inexorably picking at the stuff of the earth to return home. Canyons are a river dream manifested.

Tom drives a Ford Ranger the color of unwashed denim and I have to haul myself into the front seat by grabbing the handle over the passenger door. We drive for an hour, listening to Bob Marley before finally stopping at a gravel pull-off on the edge of a cliff; the small curve of the shoulder barely wide enough to hold the truck before plunging into a vast sea of stone, rolling and piling on top of itself all the way to the horizon.

I stand at the edge of the road taking in the dimpled desert anatomy. Piles and layers of time erode into sinuous lines of rippled stone. We are parked on the hem of the desert which feels like being parked on the hem of the world. My eyes trace the thin folds of the landscape.

Tom says, "Let's take a before picture." So we bunch together in our wetsuits, neoprene skins glistening. He outstretches his arm for the photo and I think, staring at our own ridiculous faces on the screen, that we look like sea creatures tossed carelessly into the desert.

I fasten a harness around my waist again and wrap weighty lengths of rope across my shoulders as Tom points to a wall of striated sandstone. "The canyon is on the other side," he says.

Desert streams comprise only one-millionth of Earth's water, yet they possess a relentless thrill to grind the earth down into channels of return. On a normal day, a desert stream like the Virgin carries 120 cubic feet of sediment. A monsoon flood event can cause the same stream to carry 240,000 cubic feet of sediment. Meaning one resolute storm can elicit more erosion in an afternoon than that river can carve on its own in five years.

A desert stream is simultaneously the refuge from a July heatwave and a vein that throbs in seconds with enough water to resemble the force of a freight train. A summer thunderstorm can drop four inches of rain in under 15 minutes. A dry, navigable riverbed one moment can pick up trees and boulders and bodies in the next. Desert streams are hurdled, rushing, gushing, tumbling, plunging across the stone earth, pulsing through the narrow channels of the landscape. A juxtaposition of slowness and torrential speed. Formed over millennia, yet altered permanently in a day.

Our hike to the canyon is brief, but still I feel like a blubbery seal waddling through the stone in my new thermal skin. I climb the sandstone wall, nearly on all fours, and the heat of the late desert morning slips between my skin and the wetsuit. Streams of sweat run down my back.

The day is hot and cloudless and the weather report calls for no rain. Still, I watch the sky for signs of betrayal. When we arrive at the edge of the canyon, Tom ties the expert knot at our waists before rigging up his own harness. Meanwhile, I am slow-boiled beneath my wetsuit. Standing on the edge of that maze of red stone, I look down into the slot where a black run of shallow snowmelt gently pours between the walls. I imagine parting the canyon like curtains.

In the southwest corner of Utah, water is delivered to the desert in one of two ways: from winter frontal storms that slump hunks of snow on the edges of canyons, or from summer monsoons which unload just about anywhere they please. You can always trace desert water back to one of these two origins.

Snow willingly transforms into groundwater, slipping through Navajo sandstone until captured by a less porous firmament or bumping into the denser Kayenta Formation. From there, gravity coaxes it out to face the desert as weeping canyon walls and steady fodder for the rivers. Snow is a slow bleed seeping into land.

The summer monsoons have a different tone. They are ritualistic explosions. Eruptions from the heavens. They come all of a sudden, or not at all. They dump great buckets from the sky, hurling water to the earth, slinging the floods across sandstone and pouring into rivers where they swell into a rising mass, taking out anything that stands in their path. Experts say that flash flood victims don't often die from drowning, but from the bludgeoning of objects the flood is capable of carrying.

Tom and Anna know this. Still, I want to ask one more time as we crest the final sandstone wall if it's possible to think of anything else as we leave the truck behind.

But I don't say anything. Instead, I itch at my skin through the wetsuit and Tom loops our ropes to a metal ring embedded in the rock. He double-checks our harnesses, gives us the instructions on rappelling once more, then steps to the canyon's edge. He leans back, dangling effortlessly over the 30-foot drop and reminds us, once we rappel in and pull the ropes through, we have to finish. There is no climbing out. Which means if there is any sign of rain, any moment of doubt, we have a very narrow window to jump down the three descents and swim like hell for the exit.

Before the publication of Aristotle’s Meteorology, "meteoric" was interpreted as "astronomical discussions." A great heavenly host of deliberators contemplating what weather to rain down upon the earth. As if to say a flash flood could only be brought down from the sky following a whispered debate above our heads.

Modern Earth sciences transformed "meteoric" to simply mean "any notable changes appearing in the sky." The weather would do as it would according to science with no other inputs. It really came to mean there was no one to blame but your own sorry self for not looking up in time.

Staring down the canyon, I still hope some astronomical body can hear me.

Tom rappels first and drops to the damp sandstone with ease. Anna follows and I am left alone on the ledge. Tom calls from below directing me to walk backward and approach the edge. I turn around, desert drifting by in reverse, clutching the rope so hard my hands ache. Below Tom holds tight for a steady belay while I stare up into the blue sky, looking to the corners of the horizon. I press hard with both legs and leap.

On September 14, 2015, several unexpected storms drop half-an-inch of rain an hour straight into Zion’s narrow network of gorges. The reports call it a ghost rope, that haunting strand dangling down the final ledge of Keyhole Canyon. A day after the flood, a group of three, not unlike ourselves, waits at the top for the rope to pull through, but it never moves. The three find the body of Gary Favela in the muddy pool at the bottom, face down and white.

Seven people die in Keyhole that day. The media call them the Keyhole Seven––a darling name that perhaps belies the tragedy. Over the course of an hour, by some estimates as quickly as 15 minutes, their lives are extinguished in between those stone bodies. What takes unfathomable time to carve down stone takes only moments to carve down a human life.

Tom works with search and rescue to recover the bodies of the Keyhole Seven at the end of his season. He tells me the Park Service offered him a little time off to recover emotionally. I say, “I’m sorry.” He says, “Thank you for reaching out.” We never talk about it again.

The photo so many news stations use to report the tragedy is one of the group huddled up next to a sandstone bluff. It’s nearly exactly where we stood for our photo. It is impossible to stop myself from returning to their image and ours. I spend boundless hours comparing the lines around our too-similar toothy smiles.

Can a cocked head and forced cheese of a smile capture a premonition? Perhaps if I look closely at both photos, I might see something in our faces that will reveal the events that follow. Perhaps I will understand why it could have been us, but wasn’t. In the same way a geologist reads layered stone to tell the story of the Earth, I want to believe I can read the faces of the three who lived and the seven who didn’t and see the story already written down in the creases of their eyes. But there's nothing to uncover.

Anthropologist Richard Leakey says if the Earth’s age were a thousand-page book, all recorded human history would fit easily on the last line of the last page. The accumulated lives of the Keyhole seven, our handful of hours in the canyon, wouldn’t even amass a fraction of a letter in the last sentence on the last page. Still, I feel as though we’ve been a part of geologic history.

Someone, maybe Tom, deletes the photo from the Internet before I’ve saved it and so the image disappears into the recesses of our collective memory the way the floodwaters return to a trickle just a day after the storm.

We complete the canyon in three swift jumps that take just a little under two hours. The final descent drops into a deep pool of black snowmelt, making the wetsuits entirely necessary.

A final time, I follow Tom and Anna and plunge into the water. I allow my head to submerge and the desert artery consumes the sky. My chest contracts. My sternum pops. My diaphragm spasms against the shock of freezing water. There is a terrific moment where I see the sun sparkling on the wall of water above me. I kick my legs and break the surface with a gasp.

Together, we swim through the narrow passage to the edge of the canyon, walls melting down like mountains into plains, and emerge from the water like fish taking their first steps onto land. On all fours, we scrape our sluggish bodies onto the earth. I unzip my freezing wetsuit to my waist, slide the soaking sleeves from my arms and wait for the sun to warm me.

Returning to the truck, the desert seems different; the way a stretch of road might after you survive a car crash in that very spot and walk away bewildered but unscathed.

When I return to the sandstone house, I head straight for the communal showers and crank the temperature to boiling. Water explodes from the showerhead, steaming the bathroom. The scalding rain pours over me for a long time. First I squat, putting both hands on the tile floor while the shower gushes, before finally laying down, knees beneath me, arms wrapped tight around my chest. I can't rinse the chill from my body. I can’t wash the desert water from my skin.